Dementors are evil, rat-fucking bastards, and they are real. I’ve been doing battle with them for almost as long as I can remember, even before I had a name for them.

Dementors are evil, rat-fucking bastards, and they are real. I’ve been doing battle with them for almost as long as I can remember, even before I had a name for them.

My doctor and therapists have used more clinical terms, of course—depression, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD—but J. K. Rowling’s depiction of horrid, rotting, terrifying beings that can suck the soul out of your body via a kiss seems much more accurate, especially to a nerdy English teacher who sees metaphor and symbolism in everything. For 51 years, I have managed to escape a direct attack, but living with dementors means that even when I cannot smell their foul breath and feel a rotting hand on the back of my head, I can often still sense their presence. As they lurk outside the castle gates or sneak a bony finger through a gap in the wall, they cast a pall on everything around me, dulling my taste buds, dimming the sun on even the brightest of days, demanding all the energy I can muster to keep pretending that life is just swell, thank you very much, when everything feels meaningless and everywhere feels empty.

Rat. Fucking. Bastards.

And for much of this year, those bastards have been winning. Every damn day seems to bring a new horror courtesy of Trump & Co. We’re putting babies in cages, casually dismissing expressions of white power by our leaders, ignoring the deaths of thousands, and treating 1984 and The Handmaid’s Tale as how-to manuals. Watching the country descend into fascism would be depressing enough on its own, but national calamity has coincided with a variety of “this really sucks” personal circumstances. An act of betrayal in early spring upended my vision—in retrospect, my delusion—of what the rest of my life was going to be like and with whom I was going to spend it. I still haven’t found all of the shattered fragments of my heart, much less put them back together in any recognizable fashion. At the end of May, the boy’s car was totaled; the accident was not his fault, and most importantly, no one was hurt, but the next five weeks featured a constant cycle of dead car drama. In June, a serious reaction to an ant bite metaphorically brought me to my knees and literally kept me confined to the couch for almost three weeks. Multiple trips to the doctor, a five-hour visit to the ER, and an abundance of steroids and antibiotics (intravenous, oral, and topical) eventually took care of the cellulitis infection caused by the ant bite, but they also made it impossible for me to sleep for more than a few hours at a time or to concentrate on anything for more than a few minutes. As of July, I’ve taken on a second job. It’s a good one, with good people, good pay, and manageable hours; I am immensely lucky and grateful to have found it, and I’m starting to feel like I actually know what I’m doing. But it’s also a daily reminder that, after almost twenty years as an instructor at the university, I am still not making enough to survive on my own and to provide my son with the kind of life I want him to have. It’s a daily reminder that the rest of my life is going to be about working multiple jobs just to make ends meet. My retirement plan is working until I die, and it’s become clear that I will likely die alone.

In short, the dementors have me curling into a ball in the corner. They have me convinced that being human, being alive sucks. It sucks for everybody, and I know that the ways in which my human life sucks are trivial in comparison to the challenges that most other humans face, and that I am supposed to be grateful and focus on the positives—that I had cellulitis, not cancer, that I am tutoring rather than, say, digging ditches, that good insurance coverage softened the financial blow of the boy’s wreck, that being unceremoniously dumped (again) did not also require the services of a divorce lawyer. Intellectually, I get all of that. Dementors don’t give a shit about the universality of the human condition or logic or perspective or gratitude, though. They cannot count blessings. They revel in each seemingly minor blow, and they circle in more closely, blocking out all the light, growing stronger with each well-intentioned “at least” comment. (Aside: when someone is battling dementors, never, ever suggest that things could be worse; dementors warp the message “cheer up—you’ve got a good life” into the much-less-helpful message of “you have no right to feel this way or to complain.” Dementors thrive on guilt and shame.)

So what does all of this have to do with undertaking the ridiculous project of teaching my literature students to embroider? Everything. Creating might not help allow me to conjure a fully formed patronus, but it might, just might, be enough to push the dementors away from the gate.

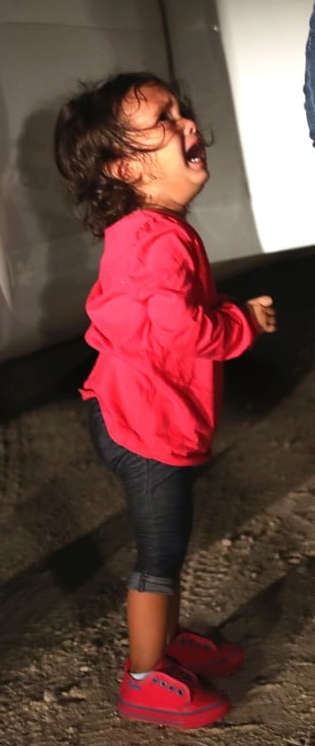

My assigned summer class was scheduled to start the second week of July. Several times during the ant-bite debacle, I was tempted to give up the course so that it could be assigned to someone else and so that I could continue to hide on my couch or in my bed for the rest of the summer. My bank account and the impending fall tuition bill from CBU would not allow such a foolish luxury. In the weeks before the term began, I roid-raged and pouted and cried and paced as I sketched out ideas for the course syllabus in my head, but it just wasn’t coming together in a satisfying way. I needed this class to be memorable for both me and my students, not just another gen-ed credit for them to get out of the way. I wanted to help them see that literature is about being REAL, about being human, about battling dementors, about sharing our humanity with each other. This desire felt all the more urgent when I saw that my class of 30 was almost evenly divided between American-born students and international students; it was the most diverse class I have ever had, with over a dozen students (or their parents) from Mexico, China, Vietnam, Laos, the Philippines, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and Canada. It was a microcosm of the planet, a microcosm of what our country could be if we were not so intent upon making sure that anyone darker than Fenty 190 Neutral was banned or locked in a coffin or a cage. It was, in fact, the image of a brown child destined for a cage in south Texas that helped my plan for the course come together. This one:

There, in my Twitter feed, was image after image of a terrified toddler who was supposedly such a threat to American safety and well-being that she and her mother were to be detained in cages. Immediately, I thought of Ursula K. LeGuin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” her dystopian story of a thriving community whose very happiness was dependent upon the continued misery of a child locked away in a cage in a dark basement. Lois Lowry cites this story in a speech that I have assigned to my Children’s Lit students many times, “How Everything Turns Away.” Lowry argues that the purpose of literature –even literature intended for children—is to encourage, even force us to look at what it means to be human, dementors and all. To face the things that cause us pain, to see the things that connect us to each other—to NOT turn away. That speech, along with LeGuin’s story and Lowry’s The Giver became the foundation for the course theme of “Time, Memory, and Legacy” and for all of my choices of reading selections for the class.

The same week that the little girl dominated my Twitter feed, another story—this one much more positive—popped up amidst images and tales of shame: a story about an amazing group of women (https://www.theanacollection.org/) who have started creating embroidered dolls as a way to share the stories of real Syrian refugees and to provide income for Syrian women who have sought shelter in Lebanon. I was struck by the simple beauty of the dolls, and I wondered what a similar doll for that little girl in Texas would look like, what story it would tell. Months later, I’m still not quite sure how all of these disparate threads came together in my head (I’ll blame the steroids, perhaps), but within hours I had convinced myself that I could teach my students to embroider so that we could create not a doll but a quilt that told their own individual stories and our collective story as a literature class. For whatever reason, it didn’t matter that I’ve never embroidered before. We would all start from scratch and learn together. The task that seemed like too much to bear—going to work every day for five weeks, pretending that I had myself together, that everything was swell—became my reason for at least trying to fight back. When I am creating, when I am fired up about a new project, it’s much easier for me to resist the power of the dementors.

When I announced this project to the class that first week of the term, many of the students thought I was joking, and all of them looked at me like I was nuts (they were right). They would not read the LeGuin and Lowry works until the last week of class, and I didn’t tell them the details of how I had devised the project. Most had never even sewn a button on a shirt before, and they were anxious that their grade would depend upon creating a perfect work of textile art (it didn’t). After a few in-class workshops on the basics of sewing a button and working with embroidery hoops, their skepticism turned to enthusiasm. On workshop days, they designed and stitched their own panel of our collective quilt as we listened to episodes of S-Town, the NPR podcast that tells the story of John. B. McLemore, another lost soul battling dementors and searching for meaning in rescuing strays (both canine and human), repairing clocks, and creating a labyrinth of boxwoods in his back yard. Their panels included symbols of who they were in the summer of 2018—the flags and landmarks of their home countries, the sports that brought them to the University of Memphis, personal mementoes of beloved family members– and of the texts we examined together throughout the course: the mazes of Icarus and John B., the quilts and blankets of Alice Walker and Sherman Alexie (damn him!), August Wilson’s piano, the rose of Faulkner’s Emily Grierson.

The fabric we worked with was chosen from leftovers: scraps from my own collection of fabric from previous projects, panels cut from the “Jailhouse Rock” costume shirt I made for WordSmith several years back, and a stack of old shirts and jeans purchased for $1.75 per pound at the Goodwill Bargain Barn. The thread, needles, and embroidery hoops came from Amazon and from my mother’s own stash of leftover embroidery supplies, including a few hoops even older than I am. On the last day of class, one student brought me a chambray shirt from his grandmother’s closet. He had told me on the first day of class that she had just been put under hospice care and was not expected to live much longer. She passed away halfway through the term, and he hoped that I might use pieces of her gardening shirt in assembling our class quilt or in future projects. He even wrapped the shirt around half-a-dozen fragrant, ripe tomatoes from the garden she had started at the beginning of the spring. Both B and I could barely speak through the tears at this point, of course, but he assured me that it would be ok to cut up his grandmother’s shirt, and I promised him that I would embroider her initials—JOM–on any piece included in the final quilt. Pieces of the sleeves and the button panel from the front of the shirt form several of the filler strips between the columns of student panels, and the grandmother’s initials appear next to the grandson’s own work.

I finally finished putting the quilt together last night. My seams are crooked and mismatched, as are the thread colors I used to piece everything together (I used up the remnants of at least half-a-dozen bobbins). I wish I had taken more care in choosing the color scheme for the fabric panels the students worked with. The panels themselves are uneven, made even more so by having been embroidered by 31 different artists with 31 different interpretations of “leave about a one-inch margin all around so that your designs don’t get sewn into the seam”. I tried to arrange the panels in a rough approximation of the self-imposed seating arrangement of the students in the classroom, but the math didn’t quite work. To fill in the gaps, I included a few panels of my own. A dear friend and colleague brought me two bags of fabric from the closet of her late mother, a lifelong sewer; I chose the back panel fabric for the quilt from that stash, but it wasn’t quite big enough, so I cut in in half and patched middle with a random assortment of scraps left over from class, including my own rough draft scrap of first-attempts to learn some basic embroidery stitches. Some of the panels are unfinished, with penciled-in images never stitched over before the five-week semester came to a close. The lower left corner even has traces of a fresh bloodstain from where I jabbed my thumb with a straight pin as I was working on the final hem. The finished quilt would never, ever, ever win a contest at the county fair, but in every image, every stitch, I see the story of how my students played along with this crazy idea and how we pulled these threads together to tell our story.

I am grateful to them for helping me to fight back. Here is the visual story of our work.

You are incredible! Thank you for this – I have been fighting my own personal dementors with the traditional chocolate (sea salted dark chocolate to be specific) from the Kroger down the road. Keep on fighting them Professor Dice – love you

LikeLike

Love you, Matty!

LikeLike

My father used to tell me that if I wanted my students to really understand process, have them build something, make something with their hands. You have leveled up, in every way, past anything I can imagine accomplishing in the classroom precisely because you don’t let yourself be limited by the classroom. You push beyond the borders, push through the pain with love, imagination, and determination. You are my inspiration. Your Patonus is a mermaid, a comet, a 9-foot-tall goddess. Your Patronus is you.

LikeLike

Love you, Terry!

LikeLike

Reading this brought so many emotions to me. Your writing is inspiring!!! Thank you for allowing us to be a part of it, you are the voice of so many others who feel this way and are too ashamed to express it. Thank You again for sharing!!

LikeLike